Brain Fingerprinting Touted as Truth Meter

Scientist says guilt or innocence can be assessed by testing electrical brain waves.

By TOM PAULSON

SEATTLE POST-INTELLIGENCER REPORTER

“Brain fingerprinting” sounds like science fiction, but for one man it could be a matter of life and death.

Larry Farwell, a Harvard-trained neuroscientist who works out of a small office in the Washington Technology Center on the University of Washington campus, hopes to use the case of Oklahoma death-row inmate Jimmy Ray Slaughter to convince law enforcement officials and the courts that the technique is scientifically sound and accurate.

Farwell, whose father was a UW physicist who worked on the Manhattan Project, believes that Slaughter’s case could be a key test of legal acceptance of the technique.

An appeal of Slaughter’s case is expected to be decided by the U.S. Supreme Court, perhaps as early as this week, said Robert Jackson, an Oklahoma defense lawyer representing Slaughter.

Slaughter, who was convicted in the 1994 brutal murders of his 11- month-old daughter and her mother, is unlikely to prevail in his case before the nation’s highest court, Jackson said. But he hopes that new evidence, including the results from Farwell’s innovative and controversial new forensic technology, will at least open the door to a new argument before the state Court of Appeals.

“The technique was ruled admissible by an Iowa court,” Jackson said. “We’re running out of options and time. We’re hoping the brain fingerprinting will at least get the appeals court to stay the execution.”

Farwell said his brain-testing technique, done on Slaughter last month, indicates that the man is almost certainly innocent of both murders.

“It’s very clear that he does not know some of the most salient features of the crime,” Farwell said. “We have 99 percent statistical confidence in our results, and Mr. Slaughter just did not know some of the things that the perpetrator of this crime would have known.”

Because Slaughter’s “brain fingerprint” constitutes new evidence not being considered in the Supreme Court appeal, Farwell said, there’s a chance that the appellate court will order a new trial.

Grant M. Haller / P-I

Neuroscientist Larry Farwell and intern Lila Wallace demonstrate how his brain-fingerprinting system works. Sensors track electrical waves in Wallace’s brain in reaction to selected words and images.

That is what happened in Iowa last year for convicted murder Terry Harrington, who was freed after spending 25 years of a life sentence for a 1978 murder when the court admitted Farwell’s test as evidence of Harrington’s innocence.

It didn’t happen for J.B. Grinder, an accused murderer in Macon County, Mo. The brain-fingerprint test — requested by the county sheriff — showed that Grinder did have “special” knowledge of the murder. He confessed and was sentenced to life in prison.

“It works both ways,” said Drew Richardson, a former FBI scientist who left the federal agency to become Farwell’s vice president for forensics.

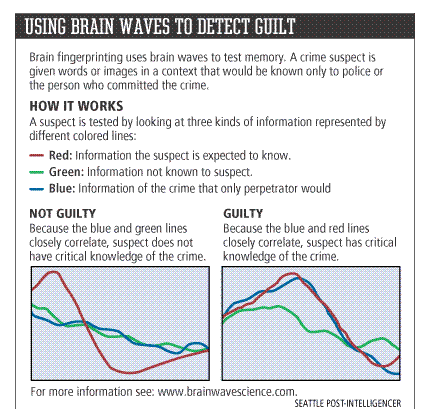

“You’re asking a suspect about information that would only be known to the guilty person,” Richardson said.

You can do that with a regular lie detector, he said, but people can easily learn how to beat the standard polygraph’s measure of stress. Brain fingerprinting, Richardson said, involves measuring an involuntary and non-controllable mental response to the information.

Farwell’s technique is based on an electrical signal in the brain known as a p300 wave. Named because it is an involuntary response to a recognized object or word that usually happens within 300 milliseconds, the phenomenon is widely accepted and not controversial within the neuroscience community.

What’s controversial is Farwell’s claim that he has figured out a foolproof way to use the p300 and a secondary, related electrical brain response — which he has dubbed a MERMER, for “memory and encoding related multifaceted electroencephalographic response” — to replace the much-maligned (and legally inadmissible) polygraph test.

“More research does need to be done on the brain wave techniques, but it’s already far better than the polygraph,” said David Lykken, a retired professor of psychology at the University of Minnesota and a leading critic of the forensic use of polygraphs.

“There is no scientific validity supporting the use of the polygraph test,” Lykken said. “It’s worse than Russian roulette.”

The National Academy of Sciences issued a report last fall that determined much the same, adding damningly that there is likely no way to improve on the polygraph’s accuracy because of the “inherent ambiguity” of what’s measured.

The blue-ribbon panel briefly touched on Farwell’s approach as an alternative, noting that it had promise but still needs more study.

Frank Horvath, a professor of criminology at Michigan State University and a member of the American Polygraph Association, said Farwell’s brain-fingerprinting scheme remains largely unproven, “There’s a lot of value in looking at brain wave activity, but there’s also a lot of hype,” said Horvath, who is also a consultant to the Defense Department’s Polygraph Institute. He said not enough research has been done to back up Farwell’s claims of accuracy, and the approach has some critical limitations even if it is shown to be effective.

“It can only be used when the investigator has specific knowledge of something that only the guilty person would know,” Horvath said. In many crimes, he said, the investigators won’t have the kind of information needed to adequately test a suspect.

Until more work can be done to establish the effectiveness of Farwell’s technique, Horvath said, it is best to stick with the proven track record of the polygraph.

Farwell, who has patented his technique and conducted published research, agrees that more studies will be needed to objectively assess the effectiveness of brain fingerprinting. But he doesn’t think this means it shouldn’t also be put to use now.

“We have a backlog of some 400 cases from people who say they’ve been falsely accused,” he said. “Should we have told Jimmy Ray Slaughter, with maybe 90 days to live, that we can’t apply this technology until everyone is convinced of the science?”

Farwell said he formed a private company, Brainwave Science, because he wanted to contribute to the betterment of people’s lives.

“I would have been happy continuing to do research, but I realized I could make a difference,” he said.

Farwell said he patented his technique almost 10 years ago but only recently decided, after initially collaborating with researchers at the FBI and CIA, to try to launch his innovation through the world of business and commerce.

The pioneer of brain fingerprinting has a pedigree that, at the very least, should make people consider that he may be on to something. His physicist father, the late George Farwell, was on the team of scientists assembled by famed physicist Enrico Fermi for the development of the atomic bomb.

“My father’s dissertation, on the discovery of plutonium-240, wasn’t declassified until the 1960s,” Farwell noted.

George Farwell, who died only last year (two days after giving a UW physics lecture in his pajamas and an overcoat), inspired his son to aggressively pursue scientific truth.

Farwell said he is, in turn, trying to use science to establish the truth.

“I realize this sounds like science fiction to a lot of people,” Farwell said. “But this is based on solid science. Once people understand the technique, it just makes sense.”

P-I reporter Tom Paulson can be reached at 206-448-8318 or tompaulson@seattlepi.com

Links

More from the Seattle PI on Brain Fingerprinting