Brain

Fingerprinting Testing

Traps Serial Killer in Missouri

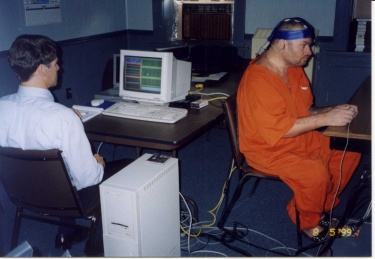

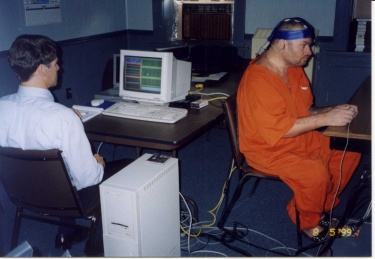

By Beth Dalbey Ledger News

Editor

THE TRUTH

SHALL SET YOU FREE -- In this case, it was

the truth that convicted suspected serial

rapist and murderer James B. Grinder, right.

The test conducted by Fairfield scientist

Dr. Farwell, left, identified Grinder as the

rapist and murderer of Julie Helton in Macon

County, Missouri, 15 years ago.

Brain

Fingerprinting Testing

Traps Serial Killer in Missouri

Technology developed by a Fairfield

entrepreneur tied a tidy bow around a

15-year-old murder case in Missouri earlier

this month.

The brainchild of Lawrence Farwell,

Brain Fingerprinting is a computer-based

technology to identify the perpetrator of a

crime accurately and scientifically by

measuring brain-wave responses to

crime-relevant words or pictures presented on

a computer screen.

Macon County, Mo., Sheriff Robert

Dawson said the state had a strong case

against James B. Grinder, 53, in the Jan.7,

1984, abduction, rape and murder of Julie

Helton, a 25-year-old Marceline, Mo., woman

who worked at a book-publishing company. Her

badly beaten body was discovered four days

after the murder near a railroad track in

Macon, the county seat of Macon County.

Grinder, a wood-cutter who had lived

in Arkansas before moving to Macon a few years

before the crime, has been "a suspect for

years," Dawson said. In 1993, court-ordered

blood samples were taken from Grinder and

another suspect - Wilford Swank, a former

Macon city policeman free on bond as he awaits

trial for first-degree murder - but at the

time, there wasn't enough evidence to indict

them.

Grinder and Swank were arrested in

March 1998 when Grinder was released from

prison, where he had served time on an

unrelated charge. Granger had confessed his

involvement, but authorities wanted to make

sure "we had the right guy," Dawson said.

Dawson recalled news coverage of

Farwell's patented technique and gave the

founder of Brain Wave Science and the Human

Brain Research Laboratory in Fairfield a call.

On Aug.5, Farwell tested Grinder's brain for a

memory of the 15-year-old murder.

"There is no question that J. B.

Grinder raped and murdered Julie Helton,"

Farwell said after the test. "The significant

details of the crime are stored in his brain."

For investigators Brain

Fingerprinting testing provided a measure of

reassurance.

"I think she was planning on

pleading guilty, but the test confirmed to us

that we had the right guy," said Dawson. "He

told us prior to testing he had committed the

crime, but we were trying to verify that."

On Aug. 11, 6 days after crime-scene

specific messages were flashed before him,

Grinder pleaded guilty to first-degree murder

in 44th Judicial Circuit Court. He was

sentenced to life in prison without the

possibility of parole, and was immediately

transported to Arkansas, where he is a suspect

in the murders of three other young women.

Farwell's technology had proven 100

percent reliable in more than 120 tests on FBI

agents, tests for a U.S. intelligence agency,

and for the US Navy, and test on real-life

situations, including actual crimes.

"The accuracy rate so

far has been 100 percent," Farwell said.

"All scientists know nothing is ever 100

percent, so I don't tout it as 100 percent

accurate technology, but I do have high

statistical confidence in it."

The Grinder case was "the first time

I've been called in on an active criminal

case," said Farwell.

Grinder had confessed to

authorities, but "the difficulty was this

suspect had told many different stories many

different times," Farwell said. "At times, he

had actually confessed, but he later testified

and contradicted himself.

"What his brain said was that he was

guilty," the Fairfield scientists said. "He

had critical, detailed information only the

killer would have. The murder of Julie Helton

was stored in his brain, and had been stored

there 15 years ago when he committed the

murder."

In terms of the advancement of his

technology, the test on Grinder's brain

represents a huge step forward. It's proven

technology in the laboratory, in studies for

the U.S. government, in studies on FBI agents

and in studies on a wide variety of different

times of information," the scientist said.

"What I did in the J. B. Grinder case is to

prove the technology can detect the record of

a crime stored years ago in the brain of the

suspect."

"We can use this technology to put

serial killers like J. B. Grinder in prison

where they belong," he said.

There are hurdles to be cleared, the

admissibility of Brain Fingerprinting evidence

in court primary among them.

Farwell points out the primary value

of the technology is to "identify the

perpetrator," but he said that "if it can be

used as evidence in court, that's an

additional benefit."

"I have every reason to believe it

will be viewed the same as DNA," Farwell

continued, explaining the DNA evidence is

regarded as scientific and highly accurate,

making it admissible in court. By the same

token, Farwell believes his Brain

Fingerprinting is equally "objective and

non-invasive."

"Anytime

you have a new invention, there are some

elements of status quo that are going to

resist it, and this is no exception," said

Farwell. "It's not only perpetrators who

resist it, but also people who are locked

into outdated ways of doing things who don't

like to see new inventions come along that

might put them out of a job."

"We're not reading minds here, just

detecting the presence or absence of specific

information about a specific crime," Farwell

continued. "The only people scared are the

people who are criminals--and that does

include some people in high places."

The creator of the technology

believes it will eventually revolutionize the

manner in which suspects are identified and

interrogated and, thus, pursued or dismissed."

"Now, if we have information about a

crime can we have a suspect, we can determine

scientifically whether that information is

stored in that brain or not," Farwell said.

"It is not only perpetrators who

resist it, but also people who are locked into

out-dated ways of doing things who don't like

to see new inventions come along that might

put them out of a job.

"We 're not reading minds here, just

detecting the presence or absence of specific

information about a specific crime, "Farewell

continued. "The only people scared are

criminals - and that does include some people

in high places."

The creator of the technology

believes it will eventually revolutionize the

manner in which suspects are identified and

interrogated and, thus, pursued or dismissed.

"Now, if we have information about a

crime and we have a suspect, we can determine

scientifically whether that incriminating

information is stored in that brain or not,"

Farwell said. "This means not only that we

bring perpetrators and protecting society from

the further crimes they might commit, but it

also serves the cause of human rights by

giving an innocent individual the means to

scientifically prove his or her innocence.

"It could save people not only from

perhaps false conviction and punishment, but

also from the trauma of investigation and

interrogation."

From Farwell's point of view, he is

serving two masters with the development of

Brain Fingerprinting.

"There are two kinds of intrigue,"

Farwell explained. "One, I have always been

fascinated with the brain, how the brain works

and how the brain reflects consciousness."

"There's another kind of intrigue,

and that is, I like catching the bad guys in

bringing them to justice. I think that's a

very important thing to do... I was very happy

to see J. B. Grinder go to prison for the rest

of his life. He killed a number of young

women. I was happy to be part of that healing

process once and for all."

How quickly the technology becomes

as routine in criminal investigations has

securing a crime scene is tied to "how

open-minded, creative and intelligent the law

enforcement community is," Farwell said.

"The question is not

whether Brain fingerprinting will become a

central facet of law enforcement in this

country and worldwide, but when and how long

it will take," he said.

"Locally, it scores very well," said

Farwell, noting as an aside that Jefferson

County Sheriff Frank Bell has embraced the

technology "very much to his credit."

In the central Missouri

County where Julie Helton's family waited 15

years for justice, Sheriff Dawson also gave

Brain Fingerprinting testing high marks.

"I would say there is a lot of

potential for something like that," said

Dawson. "I don't believe it's admissible at

this time, and that's a big hurdle, but

anytime you have got something that's going to

help you ID the perpetrator of crime, it's

going to be helpful. There are not many

investigative techniques that are 100 percent

accurate."

What Dawson would really like to see

happened is for Swank, Grinder's co-defendant

in the first-degree murder case, to agree to

the procedure. Swank is maintaining his

innocence and Dawson doesn't believe he will

submit to Brain Fingerprinting testing.

Dawson said that during his

sentencing, Grinder named Swank as a

co-defendant and also implicated two others,

brothers Todd and Charles Blakely. Charges

also have been filed against the Blakely

brothers, but were dismissed due to lack of

evidence.

Farwell said that as word of his

technology spreads through the law enforcement

community, he is receiving more requests to

test subjects in criminal investigations.

"There are a number of cases I am currently

working on that I can't talk about," he said.

He sees the application of the

technology as carrying the potential to reach

beyond the law enforcement community.

"People who are afraid of this

technology are perpetrators who don't want to

get caught," Farwell said. "Because this tests

the brain, it can catch some of the high-level

perpetrators like crime bosses who master

minded the crimes, but don't ever get their

hands dirty.

"It can also catch crooked

politicians," he continued. "I would like to

believe there are few of those, but the ones

there are ought to have something to worry

about."

Farwell says "there's really not a

downside to this."

"What it does is, it

gets out the truth," Farwell said. "The

truth will set you free. Truth has value in

any circumstance."